3 Steps to Improving Your Crop or Livestock Rotations and Building Soil Health

Note to Diversified Livestock Producers:

You may be growing some of the feedstocks your animals require, and rotating your animals across several fields or pastures. While the examples I share below are focused on crop rotations, this framework can be utilized for livestock and/or forage rotations.

What is a Crop or Grazing Rotation?

Here are three working definitions:

The practice of growing different crops in succession on the same land chiefly to preserve the productive capacity of the soil.

- Merriam Webster

Rotation is the practice of using the natural biological and physical properties of crops to benefit the growth, health and competitive advantage of other crops. In this process the soil and its life are also benefited. The desired result is a farm which is more productive and to a great extent self-reliant in resources.

- Don Kretschmann, Kretschmann Farm

Rotational grazing is the practice of containing and moving animals through pasture to improve soil, plant, and animal health.

Unless you’re planting the same thing every year or continuously grazing the same animals in the same location with no break or rest period, you’re most likely employing some form of rotation on your land.

Why Use a Rotation?

In a word, crop rotation means variety, and variety gives stability to biological systems.

- Eliot Coleman The New Organic Grower

The sowing and movement of crops and animals across land over time is one of the oldest practices employed by farmers.

Organic farmers utilize rotations to reduce the need for expensive and labor-intensive inputs and maintain the ability to produce food, fuel, and fiber. In terms of soil health, rotations (or lack thereof), have an impact on the health of agricultural soils.

Rutgers University researcher Firmin Bear believed:

A well-thought-out crop rotation is worth 75% of everything else that might be done, including fertilization, tillage, and pest control.

Common goals for crop rotation

Conserve and build organic matter

Add nitrogen

Control diseases

Reduce labor

Reduce weed pressure

Minimize off farm inputs

Increase profits

Capture solar energy

Have a diverse product line

Economic stability

Control insects

Source: Mohler and Johnson, Crop Rotation on Organic Farms (2009).

Three Steps to Improving your Rotations

There are three steps to developing the rotation portion of your Soil Health Roadmap’s (SHR) Nutrient and Field Management Plan.

Step 1 - Review and Summarize Historical and Current Practices (What have you been doing?)

Before you jump into solving problems or change what you’re doing, it’s best to take a step back and gain perspective about what you’ve already tried.

There are multiple ways of approaching this step, but the important thing is that you commit to the process and actually write down the basics of your past and current practices.

Something powerful happens when you take the time to collect your past records, review them and physically record the key thoughts you have about your work.

The benefit of this may not be immediately obvious, but I assure you that serious reflection can reap big rewards over time.

You’ll see your work and its impact in a whole new light.

For my SHR, I crafted a few paragraphs that described the basics of my rotational practices including:

When I started using rotations

The general guidelines and relationships I followed to arrange my crops across time

Why I divided my land into ¼ acre blocks

The perceived benefit of my rotations

How (and why) my rotations have changed over the years

I then summarized in a table (a drawing would have worked too), what my rotation looked like each year for the past five years.

My rotation grouped crops by plant family, so I also put together a table that showed the percentage area of my field devoted to each plant family and how that had changed over the last 5 years.

These tables helped me understand what crops were dominant in my rotation based on how much land they required in a given year and how much fluctuation occurred annually.

It also gave me about how market-driven my rotation was. I used to sell to restaurants, grocers, and direct through my Community Supported Agriculture CSA program.

Because I grew a few crops in larger quantities for my wholesale accounts, my rotation was lopsided and changed drastically from year to year as the market demand changed. By contrast my CSA market necessitated smaller quantities and more diversity.

After reviewing what I’d summarized about my historical rotation practices, I realized how the instability of wholesale accounts had caused me to compromise my rotation (and thus soil health). This step of building my SHR reaffirmed for me the value of a more balanced, diverse cropping plan.

Now It’s Your Turn

The questions and ideas below will help you prepare an overview of your historic rotational practices. If you have more than one rotation, work through the following questions for each rotation.

How are animals and/or plants moving across your land both spatially and temporally?

Look at an aerial map of your farm that shows the sub-fields/sections of land that make up your rotation. How did you decide on these delineations? Are they roughly equal in size or is there a wide variation?

How do you currently group your rotation, perhaps by plant family, time of sowing, or age of livestock?

What is the typical length of your rotation? Has it changed drastically over the last few years?

Do you incorporate a fallow or soil-building break between market crops? Why or why not?

Prepare a summary table or draw a map showing your rotation(s) for the past few years. Make notes as to how it has changed over time. What were the key drivers of those changes?

Prepare a table showing the annual percentage of area devoted to each group or segment of your rotation. How have the percentages changed over time?

Over the past few years, have you changed how you group the crops or animals in your rotation? If so, why?

Step 2 - Identify Challenges and Opportunities (How well has what you’ve been doing working?)

Once you’ve taken adequate time to synthesize your past practices, you can begin to outline the challenges and opportunities to improve your rotations.

Go back to your historical summary and review the key drivers of your rotation.

Is the timing or diversity of your rotation(s) constrained by space, field conditions, labor challenges such as saturated or compacted soil, heavy weed pressure, etc., stocking densities, or a lack of accessible markets?

Are there logistical challenges that are hindering production?

Do you lack equipment, tools or other resources that are causing inefficiencies in your rotation? For example, is your tractor not appropriately sized to quickly move field houses or pastured shelters? Do you lack irrigation in certain areas of your rotation that cause challenges for certain crops? Write these ‘pain points’ down.

Have you made a lot of changes to your rotation every year or few changes? What is driving these changes?

Year after year, does your planned rotation fail to match what actually happens? If so, what is the root cause?

Looking at my historical practices summary helped me see that my rotation wasn’t pragmatic from the beginning. I had nine field blocks in a rotation based simply on crop family.

But more often than not, I couldn’t plant into four of those blocks in early spring because they weren’t well drained. On paper, my rotation looked great.

But by early April, I’d be scrambling to disc and prepare other sections of my field so I could maintain my spring planting schedule because there was still standing water in the blocks I had intended to use. Not only was this stressful, it was also terrible for soil health, because some years, I’d try hard to get those low-lying fields worked up properly.

By using other sections of my field, I was completely overturning my planned rotation scheme- meaning I had to plant some crops in the same section of the field over and over.

Doing this was concerning to me because I did not want to cause a buildup of pests and disease.

I was caught between two poor choices and as I thought more about my rotation, I realized that spring was always the time I felt the most stressed. So I identified this aspect of my rotation as my biggest challenge.

My planned crop rotation was focused on grouping plant families regardless of planting date.

But the physical characteristics of my fields coupled with seasonal weather patterns were, in all actuality, the primary drivers of my rotation.

Swine at my farm have historically been pastured in paddocks and not rotated through market crop fields. In 2017 I suspended the heritage pork programbecause my grazing rotations were not well managed and I was concerned about a degradation of soil health.

Instead, I planted the paddocks to a mixed species orchard. (Pear saplings, shown above, are enclosed by deer fencing.) By multi-stacking functions, I hope to provide an enriched environment for re-introduced livestock, expand perennial crop production, and reduce imports of livestock feed.

Hidden Opportunities

Now that you’ve written down the challenges (Yes! Actually write them down!) go back and look at your Self-Land-Community venn diagram that you created after reading the Self-Land-Community Framework for diverse farms blog post.

Think about your personal goals, the health of your land, and the needs of your business as they relate to crop and grazing rotation practices on your operation.

SELF

What are the primary goals you have for utilizing rotations as a tool for your diversified operation?

Take a look at the perceived benefits you listed above.

Are you achieving those benefits?

Are they valid in light of what you now understand about your operation?

If not, take time to identify the primary reason(s) you’re motivated to use rotation as a tool and what specifically you want to achieve.

When you think about your rotation, are you proud of your practices?

What would you personally like to be doing/trying/changing?

What would you like to stop doing?

Do you enjoy planning and implementing your rotation or is it a stressful element of your work? Regardless of your answer, can you elaborate on what specifically it is that makes you feel that way?

LAND

Where does soil health fall in priority relative to the key drivers you listed in your historical practices?

Are there aspects of your current rotation that are clearly improving the health of your land?

What would an ideal rotation look like from the standpoint of your soil and/or pasture health?

COMMUNITY

Think about the markets you serve and how they relate to your rotation.

Are these two elements of your system aligned or at cross-purposes?

Are there crops or animals that would add value to your rotation and serve a market need?

When you’re thinking through the challenges and opportunities of your rotation, it can be tempting to skip ahead and try to come up with solutions at the same time.

Resist that urge.

At this step, try to get clear about what is and isn’t working and about your underlying motivations and true goals.

Don’t disregard possible ideas because you can’t yet see any feasible way to implement a solution or “fix” a challenge.

Before moving onto step three, summarize your challenges and opportunities in a few simple bullet points.

For each of your challenges, can you identify corollary opportunities?

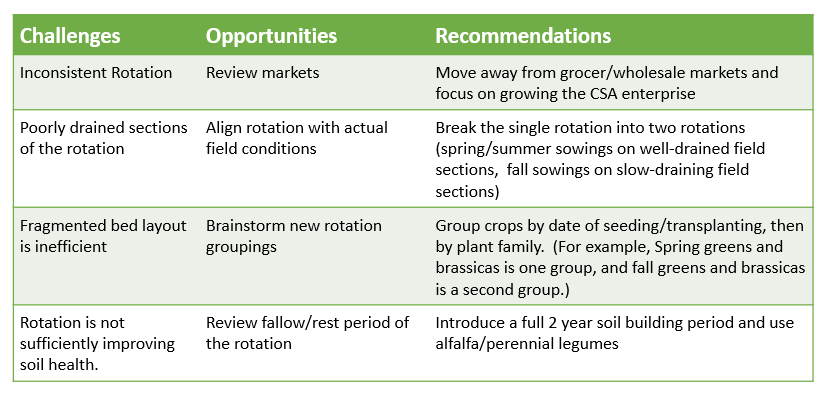

Here’s an example from my farm.

Step 3 - Brainstorm Potential Recommendations and Discover Strategies and Resources for improving your Rotations.

Given the historical perspective, challenges and opportunities you’ve outlined, what improvements to your rotation are you interested in making?

This is the time to learn more about what other practitioners are up to! After putting together your historical summary and crafting your list of challenges and opportunities, it’s time to hit the books.

Reviewing comprehensive guides, reading farmer case studies, perusing industry publications, all with your particular situation in mind is a powerful way to build your farm’s capacity.

This is a form of practical research that can help you develop a robust and creative list of recommendations. It works, because you’re focused on learning with a specific purpose.

Remember, you don’t have to read every section of every book. Let your curiosity lead the way.

Dive into the sections that you find most interesting, and keep a spiral notebook or electronic notepad near at hand.

Record any recommendations or ideas that strike you as worthwhile and applicable to your operation.

Your list will form your recommendations.

Here’s a resource list to get you started:

Crop Rotation on Organic Farms A Planning Manual, Charles L. Mohler & Sue Ellen Johnson, Editors (See Chapter 7)

The Art and Science of Grazing, Sarah Flack

The New Organic Grower, Eliot Coleman, (See Chapter 7)

Building Soils for Better Crops, Magdoff and Van Es, (See Chapter 11)

Holistic Planned Grazing, Savory Institute

Weed the Soil, Not the Crop: A Whole Farm Approach to Weed Management, Anne & Eric Nordell.

Sustainable Vegetable Production from Start-Up to Market, Vern Grubinger

Rodale Institute Crop Rotation Trials, Integrating Livestock into Your Crop Rotations

Planning A Crop Rotation, Penn State

Crop Rotation Planning in Organic Farming Systems, National Center for Appropriate Technology

Livestock-Crop Integration, Center for Sustaining Agriculture, Washington State University

Make recommendations based on what you now know and what you’d like to be doing.

Look at your challenges and opportunities list, then look at the recommendation ideas you’ve compiled.

How do they fit together?

As a result of this three step process I became motivated to pursue a few changes. Here’s a portion of the recommendations I developed:

Deciding what changes to implement on your farm. When and How?

Wait! Don’t decide on changes just yet.

It may feel counter intuitive, but at this stage of creating your SHR, don’t haphazardly decide on which recommendations you’ll implement.

After you’ve assembled a list of potential ideas, set it aside and move onto the three other aspects of your Nutrient and Field Management Plan (NFMP).

Once you’ve developed lists of suggested management changes for Cover Crops, Organic Materials, and Machinery/Equipment, you’ll revisit your potential recommendations for Rotations and evaluate each one in light of all four aspects of your NFMP.

Practice, Not Perfection

Accept that fluctuations in your rotation are going to happen! Even farmers with decades of experience report as much:

Many expert farmers do not have standardized, cyclical crop rotations for every field, yet our experts share an overall approach to design, implementing, and adapting crop sequences on their farms.

- Crop Rotations on Organic Farms: A Planning Manual.

Preparing your SHR isn’t about getting it perfect the first time. It’s about leveraging improvements for maximum impact and incremental, but powerful changes over time.

The point is to improve the outcomes that are a result of the hard work you put into your farm.

Even a small success will motivate you to keep moving forward.

Don’t skip any steps because you feel like you don’t have all the answers. You absolutely have enough knowledge and experience to get started.