Assessing Soil Health on Your Diversified Farm

Three soil indicator categories and 8 tips to consider when conducting a comprehensive soil health assessment.

“Your farm is both the product of and producer of soil. Consider your farm to be a living organism that achieves its greatest long-term productivity when its natural cycles and processes are enhanced.”

Now that we have a solid working definition of soil health, and you’ve established your farm goals, it’s time to focus on assessing the current state of health of your soil.

A comprehensive soil health assessment can be fairly involved. If you’re overwhelmed at the prospect, a great place to start is by simply writing down any concerns or observations you have about the health of your soil.

For example, I used to worry a great deal about soil compaction. But it wasn’t until I created my Soil Health Roadmap (SHR) that I was motivated enough to learn how to actually assess compaction using a simple pentrometer.

Learning how to use the pentrometer was empowering. I now have a direct feedback loop that helps me know how my management practices are impacting my soil.

If you have a specific soil health concern, use the resources listed below to find out how it your soil is typically assessed.

Monitoring just one or two indicators of soil health that are meaningful to you is better than assessing fifteen that aren’t.

For a full-spectrum approach even if you are short on time, learn how to take proper soil samples and use the Cornell Soil Health Assessment lab to complete your first assessment.

By establishing a baseline, you’ll be able to identify target areas to focus your SHR on, as well as track and monitor your progress.

Read to dive in?

Just as you might prepare and review financial reports, you can think of your soil health assessment as a balance sheet for your land.

What are assets, what are liabilities, and how much equity has been stored up?

What is the definition of a functioning, healthy soil?

From sequestering carbon to providing nutrient dense food, well functioning, healthy soil is absolutely critical to life on earth.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations defines soil health as follows:

Soil health is the capacity of soil to function as a living system, with ecosystem and land use boundaries, to sustain plant and animal productivity, maintain or enhance water and air quality, and promote plant and animal health. Healthy soils maintain a diverse community of soil organisms that help to control plant disease, insect and weed pests, form beneficial symbiotic associations with plant roots; recycle essential plant nutrients; improve soil structure with positive repercussions for soil water and nutrient holding capacity, and ultimately improve crop production. A healthy soil does not pollute its environment and does contribute to mitigating climate change by maintaining or increasing its carbon content. (FAO, 2008, 2020)

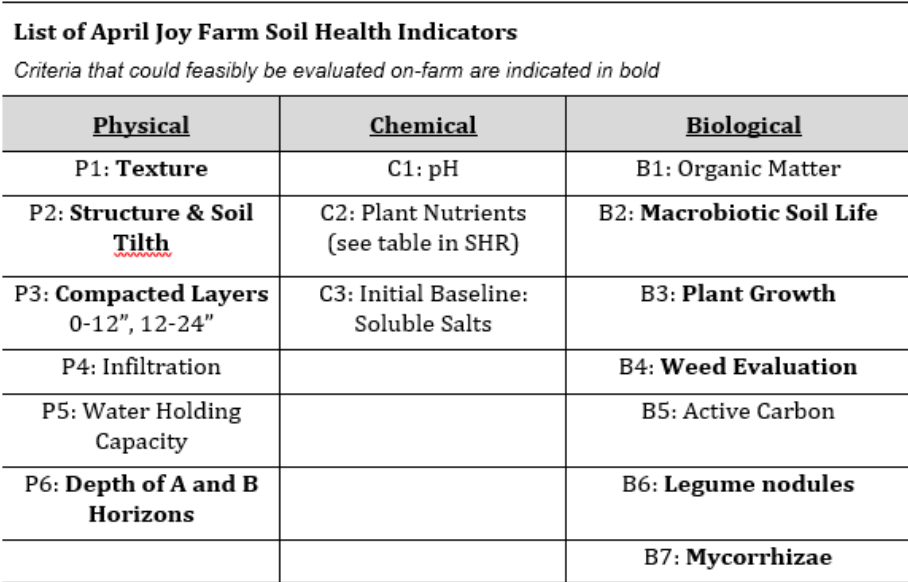

Three Categories of Soil Indicators

From a scientific perspective, soil health indicators are measurable properties that provide information about how well a soil is functioning.

While there are many indicators of soil health, all indicators fall into one of three categories:

Physical

Chemical

Biological

Physical Soil Health Indicators

The physical characteristics of your soil include its color, texture, structure, consistency, and the horizons or layers. Although many of these characteristics are difficult to change, management practices can significantly improve or decrease the ability of the soil to function properly.

For example, a well-structured (uncompacted) soil can improve infiltration and nutrient exchange, and reduce erosion.

Chemical Soil Health Indicators

Chemical characteristics commonly include the quantity of nutrients available in your soil, the relative acidity, salinity and electrical conductivity.

The information captured in the chemical portion of the soil assessment will inform management decisions about when to apply inputs such as compost to augment nutrient availability or lime to adjust soil pH.

These indicators may also influence how you manage the organic materials available to you, and possibly the crops you choose to grow.

For example, in response to a soil test revealing high levels of phosphorus, I eliminated direct applications of manure to my fields and I’m working to reduce my reliance on purchased livestock feed (i.e., the importation of additional phosphorus) by growing my own grains.

Most chemical indicators of soil health must be analyzed in a laboratory. This will require you to submit soil samples for evaluation.

Seek help from a technical advisor if you need assistance evaluating the testing procedures and/or interpreting results. It’s crucial for you to be able to identify the forms of plant-available nutrients such as nitrate, ammonium, phosphates and potassium ions (NO3-, NH4+, H2PO4- and K+), and how these values relate to reported soil test results and total nutrient values.

Don’t be afraid to ask as many questions as you need to feel confident about the results of any lab analysis.

Biological Soil Health Indicators

Common biological indicators of soil health include: organic matter, plant growth, root health, mycorrhizae, earthworm counts, active carbon, soil respiration and weed populations.

Biological indicators of soil health have traditionally been qualitative. Aside from organic matter, only recently have quantitative, lab-based methods been accessible for evaluating soil biological health.

Because you’re in your fields and working with your farm system more than anyone, you are uniquely qualified to assess the biological soil health of your land. There are a number of biological indicators you can monitor, including the density and diversity of macrobiotic soil organisms, the presence of mycorrhizae, the health of root structures, as well as how well nitrogen fixation is occurring in your leguminous plants.

Where do you start?

Learning exactly what all the different assessment indicators are actually measuring can take time. Fortunately there are a number of regionally available tools to help you identify and learn how to assess soil health indicators.

The list below provides the list of soil health assessment resources that I used to pick the soil health indicators I wanted to track for my farm. (Note: some are only regionally appropriate to Washington state.)

Soil Health Assessment Resources

How do you know which indicators to monitor for your farm?

Using these resources, create a list of criteria appropriate to your management practices and the site characteristics of your farm.

Once you’ve drafted your list, ask for input from a regional soil scientist, agricultural extension agent, USDA conservationist, technical advisor from your local Conservation District, or a mentor.

Make sure your advisor is familiar with your operation and has the expertise to be of value.

The Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) provides this useful criteria to help you choose which indicators you may want to assess:

Useful indicators:

easy to measure.

able to measure changes in soil functions.

assessed in a reasonable amount of time.

accessible to many users and applicable to field conditions.

sensitive to variations in climate and management.

representative of physical, biological and chemical properties of soil.

assessed by qualitative and/or quantitative methods.

Visit the NRCS soil assessment website to learn more about soil health indicators and access their soil quality indicator sheets.

Washington State University has an excellent overview of proper soil testing procedures for farms with diverse vegetables crops.

Deciding how to approach the soil health assessment for your operation can feel daunting.

Here are 8 tips and more resources to help:

1. Use Cornell University’s Comprehensive Assessment of Soil Health.

If you are short on time or just want a straightforward place to start, I recommend Cornell University’s Comprehensive Assessment of Soil Health Standard Soil Health analysis package.

After submitting a soil health sample, you’ll receive a detailed report that outlines the physical, chemical, and biological indicators tested.

The report also provides in-depth information about what each indicator is testing, and provides recommendations for management changes. Cornell’s excellent soil health manual is a supplemental resource I’ve found helpful.

2. Get accurate data from the right tools and expertise.

As you evaluate different indicators you may wish to assess, make sure you have the tools and expertise or lab support to get accurate data.

Also, make sure you budget for the costs involved for lab and shipping costs. To make sense of all the different indicators and help figure out what I wanted to track, download this spreadsheet I created that you can adapt for your use.

3. Identify meaningful indicators.

Remember, while it is important to identify at least 2 indicators from each of the three categories (physical, chemical, and biological), some common indicators may not be meaningful for your operation.

Erosion for example, is not a physical indicator I specifically monitor at my farm, based on the lack of historical occurrence, the slopes of my field, the existence of extensive perennial field buffers, the usage of cover crops and the timing of tillage relative to significant rain events.

A neighboring farmer with extensive winter field operations and/or more steeply sloped fields would want to include erosion as part of their soil health evaluation. Make sure you assess what is important to your situation.

Don’t test just for the sake of testing!

4. Identify correct assessment criteria and evaluation methods.

A key objective of this soil health assessment is to identify assessment criteria and evaluation methods that are accessible and meaningful for you, the farmer, to undertake, given your location, existing resources, and production methods.

While laboratory analysis provides necessary information, a healthy soil ecosystem begins with knowledgeable, astute land stewardship. That means you!

Because of the close working relationship you have with your soil, in some ways you know your soil better than anyone.

Where feasible, on-farm assessment techniques that you can monitor are especially valuable. Earthworm counts, noticing how well or poorly your fields drain after rain events, or if there are specific areas where crops perform especially well can all be important indicators of soil health.

5. Allocate time to perform tests.

Remember to allocate time in your annual schedule to perform the tests or collect samples, and keep this schedule consistent from year to year.

I add the appropriate soil assessment tasks in my annual crop schedule so I don’t have to try and rely on my memory.

Some of my tasks include: taking soil samples, identifying weed pressure four times a year (wet/cold, wet/warm, dry/cold, dry/warm), and performing earthworm counts.

6. Leverage your existing practices to help assess soil health.

Each week, I perform a field walk to inventory what’s ready to harvest and concurrently to monitor and assess for weed and disease pressure. These records are necessary to maintain my organic certification. You can also glean soil health information from existing records.

Are you tracking harvest yields? If so, you can include these as part of your soil health assessment. Are your yields increasing, decreasing or remaining stable over time?

7. Focus on incremental improvement from your baseline.

Don’t compare your numbers to other operations.

Many physical soil health indicators are oftentimes scored against a distribution of indicators measured on other regional soils. It is important to understand this evaluation is only a relative indicator of soil health because the overall health of other regional soils is not known.

A more accurate evaluation of soil health occurs when a soil health indicator is evaluated from the same location such as your farm, on a regular basis.

By tracking changes in soil health on your farm over time (not relative to other regional soils), your soil health can be more accurately assessed as declining, stable, or improving.

8. Use the appropriate technical resource to answer your questions.

I had multiple conversations with my Washington State University soil scientist advisor to make sure I understood the results of my lab reports and how they were changing over time. I also called the lab that performed the nutrient analysis of my soil samples to make sure I understood how they arrived at their results.

Here’s a complete list of the indicators I’m assessing for my SHR:

For more details on assessing soil health including my baseline measurements, download the April Joy Farm SHR case study.

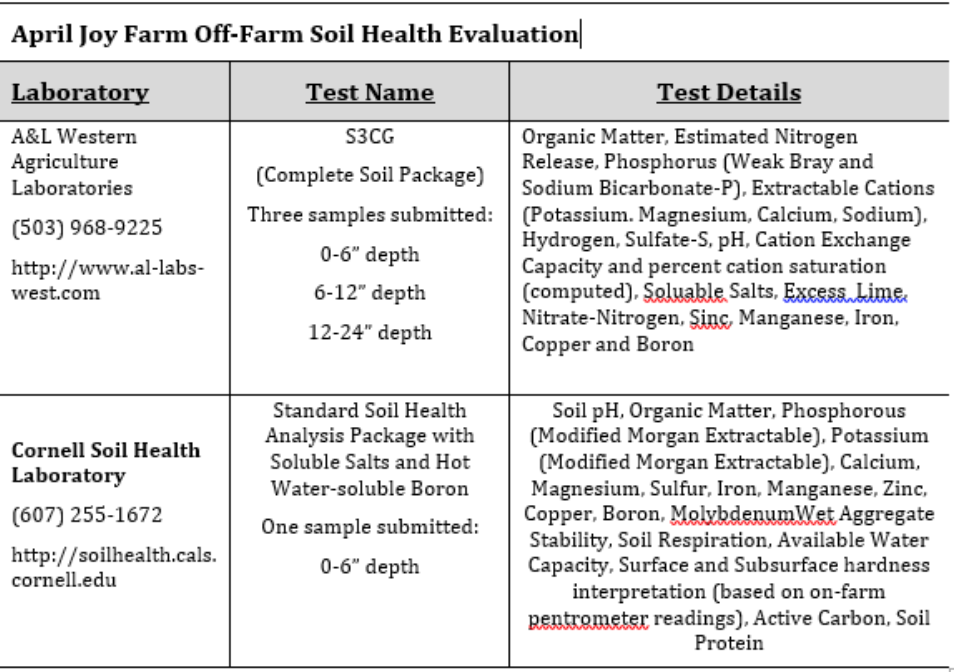

Here is the list of labs and tests I use for my soil health assessment.

The goal of your soil health assessment is to better understand both quantitatively and qualitatively how your soil is functioning, and to identify areas for improvement.

What you learn in your soil health assessment will help guide the development of your systems nutrient budget and ultimately the changes you want to implement on your farm.