7 Steps to Preparing a Systems Nutrient Budget for Your Diversified Farm

Learn how to identify if your diversified farm operation is increasing or depleting vital soil nutrients based on your current management practices.

After you’ve prepared a baseline assessment of soil health, the next step in creating a Soil Health Roadmap (SHR) is to develop a Systems Nutrient Budget (SNB).

Visualize the SNB as you would a farm pond.

Your goal is to better understand the sources and quantities of water flowing through the pond. What’s coming in, how much, and where exactly is the water coming from? Likewise, what’s leaving the pond, how is it exiting, and how much is flowing out?

Now, instead of a pond, consider your soil. And instead of water, focus on the key limiting nutrient(s) that are entering and leaving your land.

Just like you might track a bank account, the SNB is a way to identify if you are increasing or depleting vital nutrients based on your current management practices.

How much equity are you building up? Let’s find out!

7 Steps to Preparing a Systems Nutrient Budget

There are several steps to preparing a system nutrient budget, but the actual calculation of the SNB is easy. It’s all the careful preparation that takes the most time and effort.

Follow these steps to create your SNB (TABLE OF CONTENTS)

1. Determine which nutrient(s)you want to focus on

Results from your soil health assessment will inform which macro and/or micronutrients you’ll want to focus on in this step.

For instance, the soil health assessment for April Joy Farm revealed a deficiency of nitrogen and an excess of phosphorus. Brad and I decided to focus on capturing the dynamics of these nutrients.

You may choose to track different nutrients based on the goals of your production plan and the crop rotations you currently employ.

For instance, if one of your farm goals is to grow high-protein feed grain, then your systems nutrient budget will need to focus on the relatively high nitrogen demand of such crops.

Alternatively, if your farm goal is to grow alfalfa hay, replacing exported phosphorus could be a key focus.

Decide what nutrients are important for your situation by spending a little time reviewing your baseline soil health assessment from a nutrient cycling perspective. Are the values of any macro nutrients on your soil test reports very low or very high?

Think about your goals, too.

Are you spending a lot of money and time purchasing and/or applying fertilizer, compost or manure? What nutrient are you most focused on “correcting” for?

Ask trusted technical advisors or farm mentors for input as well.

If you’re new to nutrient budgeting, it’s ok to start by focusing only on nitrogen. Over time, you’ll become comfortable with the process and you can expand your SNB to include other nutrients.

2. Identify the physical and time boundaries of your SNB

As you decide what key nutrient(s) you want to focus on, consider what will be the appropriate area to include in your assessment.

For instance, on my farm, I have several livestock pastures, two orchards, a vineyard, a grazing paddock for my poultry flock, a two-acre vegetable field and a six-acre hayfield.

All of these discrete areas could be the focus of their own SNB, or I could develop a SNB that includes my entire landbase.

When you’re determining the boundaries of your SNB, remember that the larger or more diverse the area, the more difficult and time-consuming it will be to create a meaningful SNB.

Because my vegetable field is the most intensely managed aspect of my farm, I chose to limit my SNB to this area. I also picked this area as my SNB boundaries because a primary goal of mine is to reduce the off-farm fertilizers used to grow my produce.

Was I over applying fertilizer without knowing it? I wanted to find out.

The second parameter you’ll need to decide on is the timeframe for your SNB. To use our previous analogy, what period of time are you going to track the water coming in and going out of the farm pond? If you only monitor the water flows during the summer, you’ll have different data than if you assess things from December to May.

Unless you have a specific reason for doing otherwise, I would advise using a calendar year as the timeframe for your SNB. Using a calendar year will ensure you capture all the inputs and exports associated with your farming activities as well as a climate and ecosystem effects on nutrient cycling.

3. Decide on the input and export categories for your farm

The goal of the SNB is to identify the origin of deficits and/or surpluses of key nutrients on your farm so you can make better decisions about fertility management. What exactly are the ways these key nutrients are being added to your field and how exactly are they being removed from your field?

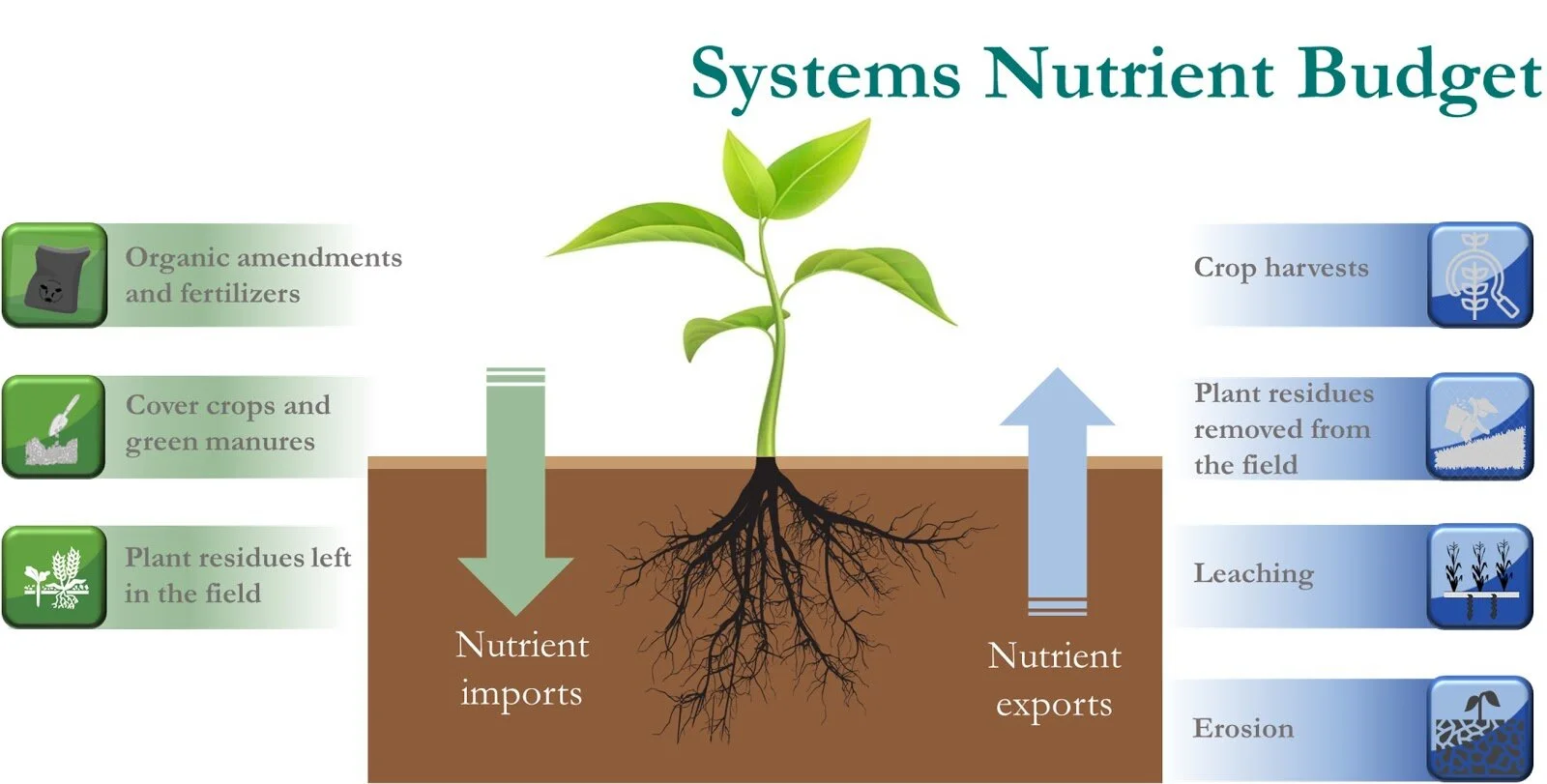

Here’s an example of some common nutrient imports and exports for a produce field.

The categories of imports and exports shown above are fairly common, but not at all comprehensive.

Also, there is a substantial difference between a simple nutrient budget and a Systems Nutrient Budget. A systems nutrient budget includes factors such as nitrogen fixation by legumes, leaching, rain deposition, and erosion, whereas a simple or “farm gate” budget includes only those materials applied or removed from the field, such as what passed in and out of the farm gate.

The items that make up the categories and their relative importance will be specific to your farm.

For example, at my farm, the category soil amendments included blood meal and manure, but you may not use either of these materials on your operation.

Likewise, leaching is a significant factor due to the 40+ inches of rain my region gets each winter, but erosion is non-existent. These factors may not be true for your operation.

Certain categories, such as plant residues, could be either a nutrient import or export depending on how you’re using them. If you remove plant residues from the field they would represent nutrient exports, but plant residues like straw, hay or leaf mulches that you apply to the field would be considered nutrient imports.

A systems nutrient budget for a livestock operation will include different elements, for instance feedstocks.

Keep it simple if you can.

There are several imports and exports I did not include in my SNB, due to the difficulty of quantifying and their assumed relative factor of magnitude. Imports that I did not calculate include: Soil & mineral solubilization, biological weathering, atmospheric deposition/precipitation.

I also didn’t attempt to estimate export loss from denitrification or ammonification.

When determining which categories to choose, include all physical materials you’re applying or removing from inside the SNB boundary you have established as well as weather and climate processes. Here are some examples:

Crops

Plant resides

Fertilizers

Manure

Compost

Meat

Milk

Eggs

Leaching

Flooding

Erosion

For more help determining your categories, see the following resources and contact your local farm extension agent or regional soil scientist.

Resources to Help You Develop A Systems Nutrient Budget

This eOrganic article on Nutrient Budget Basics for Organic Farming Systems is a good place to start as you begin creating your own systems nutrient budget.

Nutrient budgets for livestock operations will be different and include imported livestock feed. Check out this Nutrients Budgets Tool (PDF).

For my SNB, I settled on the following four import categories:

Soil Blocking/Potting Mix used for the production of transplants

Amendments and Fertilizers applied at the time of direct seeding or transplanting

Broadcast/Non-Crop specific amendments applied directly to the field (including manure)

Leguminous Cover Crops: Crimson Clover, Red Clover, Field Peas

Two export categories:

Plant harvests and residues removed from the field

Leaching

4. Gather the necessary farm records and/or estimates for each input and export category

For each category of nutrient input and export you’ve identified, you’ll need to gather the appropriate records for the entire time period you’ve chosen to assess. The records you need also depend on what nutrients you’re focusing on.

For starters, think through everything that is physically brought to or removed from the area you are focused on.

Which are known sources of the nutrient you are targeting?

For instance, even though coarse sand is an element of my potting soil mix I use to start my transplants, because sand does not add nitrogen to my field, I don’t need any records.

Think chronologically, or in terms of the phases of your farming season (seeding, growing, harvesting, etc.).

Finally, how does your climate and the natural processes that are cycling nutrients affect your nutrient systems?

Do you think water is causing a significant amount of the nutrients to be deposited or carried away through rain, snowfall, or floods?

What about wind?

Is erosion a big concern on your farm?

Are you you using any cover crops that might “import” nitrogen from the atmosphere? What nutrient scavenger grains or grasses can help prevent leaching from occurring?

Include the following recordkeeping suggestions depending on your requirements:

Harvest quantities or total yields for each product

Fertilizer and organic amendment application types and quantities, including guaranteed analysis of macronutrients

Quantities of organic mulches applied

Nutrient analysis reports from soil labs for any compost, manure, or other organic materials applied or removed from your field

Cover Crop varieties, biomass and/or quality indicators and sowing and termination records (If you’re interested in nitrogen cycling for your SNB, you’ll need to know the type and quality of the stands of leguminous cover crops that fix nitrogen. Which cover crops have symbiotic relationships with soil bacteria to convert atmospheric nitrogen into nitrogen compounds that are stored in the soil.

5 . Quantify the nutrient imports and exports by category

When you quantify nutrients, start with imports.

I use a spreadsheet or a sheet of paper to write down each of import categories, then list all the items that fall under that category.

Here’s what my nutrient import list looks like:

Soil Blocking (Greenhouse Potting) Mix Used for the Production of Transplants

Vermicompost

Kelpmeal

Crustacean Meal

Transplant Fertilizers and Amendments

Bonemeal

Bloodmeal

SoP

9-3-7

Fish Fertilizer Liquid

Broadcast/Non Crop Specific Amendments

9-3-7

Donkey Manure

Fishmeal

Cover Crops

Nitrogen Fixing Legumes

Crimson Clover

Red Clover

Field Peas

Plant Residues

Grain stalks (straw)

Grass Hay (aisle mulch)

For each item, use the records you collected in the previous step to determine two things:

What is the total quantity of the item that was applied (or in the case of cover crops the area you sowed.)

What is the nutrient analysis of each item you’ve listed?

For instance, let’s assume I’m focused on nitrogen for my SNB.

My records show I use 21 lbs of Bloodmeal for my seedling starts that are transplanted to my field. The guaranteed analysis of the bloodmeal is 13-0-0. (13% N - Nitrogen, 0% P - Phosphorus, 0% K - Potassium),

That means that I’ve imported 2.77 lbs of nitrogen to my field. (21 lbs bloodmeal x 0.13 lbs N per lb bloodmeal = 2.77 lbs N.)

You may need to use lab analysis reports for some inputs or exports. I had my donkey manure tested to determine the average N-P-K values.

Most likely, you won’t have all the farm records required, and that’s ok! The process of creating your first SNB can be helpful in exposing areas of your recording keeping that you may need to improve or refine.

Take time to figure out how to capture the data you need, because if you don’t trust the data used to create your SNB, you definitely won’t use it to make management changes.

There are some circumstances in which an estimate of the nutrient imports or exports must be made. For instance, I hadn’t taken a field sample of my clover cover crop to send to the lab so I could calculate the nitrogen fixation attributable to my cover crop.

Instead, I used an estimate provided by Oregon State University for ‘average’ plant available nitrogen values for clover.

Here’s the summary of all my inputs:

Detailed Table of Nutrient Imports at April Joy Farm in 2017.

Follow the Same Process for Your Exports

First write down your list of export categories and all the items that fall under each category. Quantify each item and determine the percentage of that item that contains the nutrient you are including in your SNB.

I only had two categories of exports:

Crops Harvested

Leaching

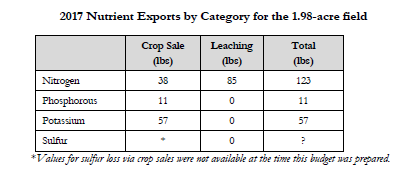

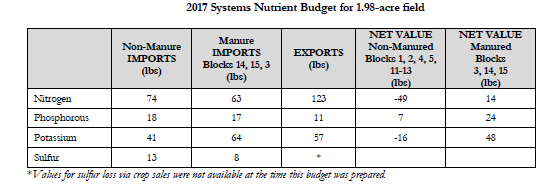

But under crops harvested, I included the top 28 crops I grow by total quantity harvested. Below is the detailed Table of Nutrient Exports at April Joy Farm.

Natural ecosystem processes can be difficult to quantify. I relied on a scientist from our land grant university to help me better understand leaching and provide an estimate.

Unless you have completed plant tissue analysis, you’ll need to estimate the nutrient profiles of your crops. Estimation will greatly simplify the calculations needed in a systems nutrient budget for your diversified farm.

The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Plants Database Nutrient Content of Crops calculates the approximate amount of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium removed by the harvest of crops.

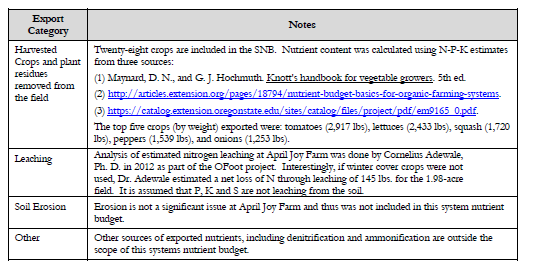

6. Calculate your Systems Nutrient Budget

Calculating your SNB is the simplest step!

First, sum the imports by nutrient. Then sum the exports by nutrients.

Total Amount of Nutrient Imported - Total Amount of Nutrient Exported = Net Value Gained or Lost

My SNB actually includes two net values, one for the areas of my field that I applied manure, and one for those without manure. This was so I could understand the impact of using raw manure in my fields. As you can see, it makes a huge difference.

For a more detailed example, check out pages 17-20 and the associated appendices of my Soil Health Roadmap. I provide an in-depth description of my methodology and the resources I used.

7. Analyze the results of your Systems Nutrient Budget

Understanding how nutrients are added and removed from your fields will help you develop targeted management practices to stabilize nutrients that are currently out of balance.

For example, my SNB revealed the farm was losing almost twice as much nitrogen from leaching as from crop exports.

Whoa! I had no idea!

Because of my SNB, and to limit costs associated with importing nitrogen fertilizers, I’ve focused on improving my winter cover cropping practices so that I can capture these nutrients before they leave the field.

Learn more about my cover cropping practices by watching the Washington State University 2020 Covercropping Roundtable. My presentation starts at 1:35 hrs into the webinar.

Click the image to watch the video.

I use a grain cover crop such as rye as it can effectively scavenge for nitrogen in the soil and prevent it from leaching. The use of legume cover crops will also help offset losses from leaching through nitrogen fixation, providing fertility to the field without adding phosphorus to the soil.

Using legume cover crops is important, because as my soil assessment revealed and my SNB further clarified, I have a surplus of phosphorus and adding manure directly to my fields exacerbates this imbalance.

I also learned that nutrient imports from soil blocking/potting activities are negligible, and do not contribute significant nutrient additions to the field. However, these imports do constitute a significant addition of organic matter for the field, including 1.4 tons of vermicompost and 0.5 tons of peat moss!

Creating a SNB is an opportunity to better understand how the various plant-available nutrients are retained and removed from soils. Biologically available forms of nutrients have very different transport mechanism. For example, phosphorous is not easily leached from soils, but certain forms of nitrogen are.

When you’re analyzing the results of your SNB, ensure you understand the ecosystem processes that are transporting your key nutrients in and out of your fields.

A SNB will help you develop a truer picture of how key nutrients flow through your farm.

Then it’s up to you to decide how you want to use that information to improve the health of your soil.